Do We Live in an Image Culture?

Words have power but how much power is the question. The ‘Sticks and Stones’ chant may teach us to ignore hurtful words from others but this still points to the impact that words can have. But in our postmodern world, the power of technology to alter the context of someone’s words has increased. For example, soundbites, which are edited versions of an original statement, are employed regularly on TV and radio…and sometimes with disastrous results.

Social Media has amplified this ability to edit or recast statements even if they do not belong to us. But there are limits. For example, the late visual communications scholar Sol Worth said Speech requires a clearly defined syntax which allows us to articulate propositions of truth and falsity. Words have to function inside a strict grammatical structure in order to be coherent. This gives humans a foundation to pursue the original intent of a statement by trying to stand outside of it to understand it. Although this does not always happen, we are dependent upon competent scholars who attempt to do this to provide us with coherent history.

But image is different. A modern online image is a socially constructed artifact and one doesn’t always know who created it. The rise of information communications technologies (ICTs) and the accessibility of image manipulation software has encouraged us to remix images from a different context and integrate them into our own. As a result, the image making industries (film, fashion, etc.) have grown in influence.

Take a look at the picture above. What do you see immediately? Will two people come away seeing the same image? (Three years ago, we argued whether the dress was blue or black or white and gold.)

If this kind of disagreement can happen with images, how can they stand in for words?

The rise of the internet and social media has provided opportunities to share words and images with others. This has opened the door for performative personalities. (Performative means a collection of expressions that leads to responses from others.) Performance, image and the human gaze have intertwined to dominate social media. It is part of the reason why we have Instagram influencers and YouTube stars.

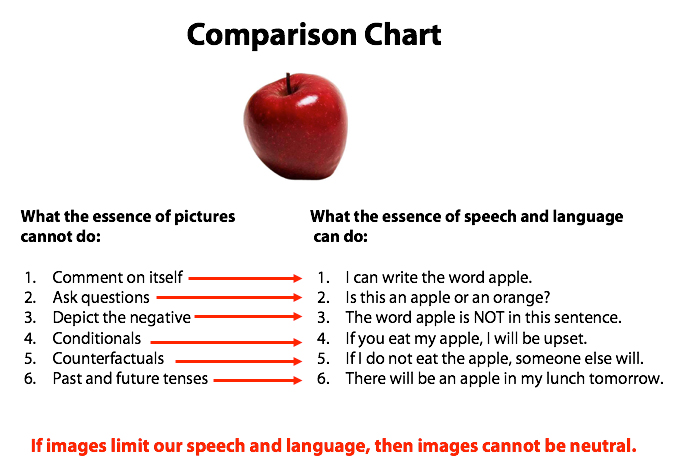

Visual images and language have always tilted towards the performative. Picture writing systems, such as Mandarin Chinese and Egyptian hieroglyphics, are descendants of images. Speech often utilizes prose, figures of speech, etc. Although this is the case, languages also have a utilitarian function because listening and dialogue are part of its existence. Images cannot do this and therefore limit our vocabulary.

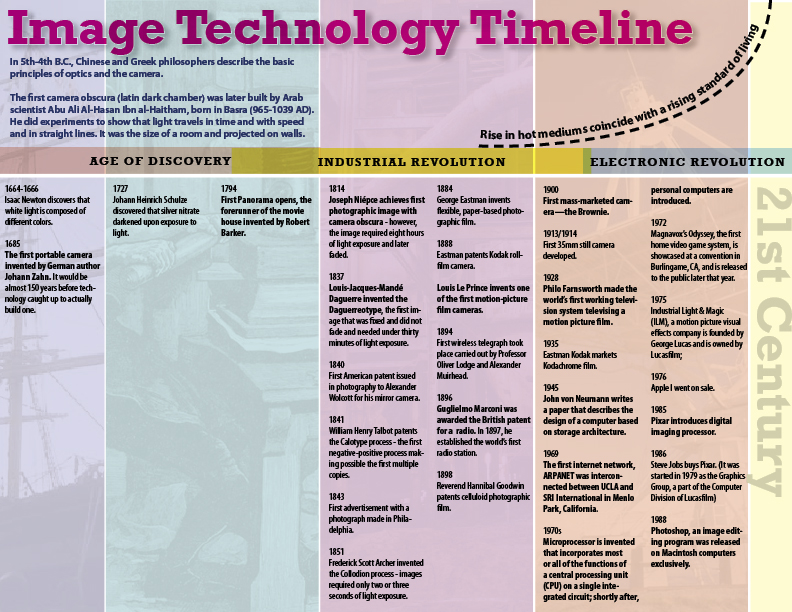

If grammatical structure did not exist in our languages, words would not mean anything coherently OR could mean anything. This is why it isn’t shocking that the first forms of technological communication that developed were based initially on language. From Morse Code to Internet Chat Relays (the first form of social media) invented in the late 1980s, expressing language by letters and marks made the technology more accessible.

But visual images, in and of themselves, are much more subjective. Humans can make their meaning and context more elastic, deeply symbolic and even mysterious compared to words. (Sidenote: Graphic designers often subvert the subjectivity of images by how we visually change and display them. For example, the universal restroom icon functions almost like language because it draws from clearly understood representational images. A company logo can also function like an icon over time depending on what it is. This is related to the field of semiotics and is not how most images online function.) Because images can appeal to different desires in each person, a picture is worth a thousand words. But a word is not worth a thousand pictures. See the comparison chart below:

It is this image subjectivity that encourages our creativity because one can define an image so narrowly that it only appeals to the individual. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, we say. Although this can reveal interesting explorations of meaning, it is also a source of great misunderstandings. (In the 1990s, Nike was accused by Muslims of making a sneaker symbol that looked like the term ‘Allah’.)

But multimedia platforms such as social media have created more problems around the use of images.

For example, several entertainers are suing Epic Games, the makers of Fortnite, for using their specific popular dance in this video game. This news is all over social media. But is popularity synonymous with ownership? Rapper 2 Milly says he invented the Milly Rock dance. Fortnite has monetized the performative nature of these dances in their video games. When we assign value to images (still and moving) based only on our individual context, it may clash with someone else’s context that seeks to re-interpret those images on online spaces. This is the outcome of a society that puts a premium on hyperindividualism. But it can cause problems, like the lawsuits against Epic Games, when one attempts to interpret and/or monetize images. How ironic is it that none of the entertainers mentioned have sued the monetized YouTube channels that give instructive tutorials on their dances.

This goes to my point: an image culture leans too much in the direction of popularity and simulacrum. On social media, the more likes and shares, the more of the same kind of images one will see. It’s performance built mainly on transactions. Of course, there are others who use images on social media for good. But in the real world, transactional relationships are not viewed solely as a virtue. They are negotiated business agreements with specific outcomes for the benefit of those involved. They can end or be terminated. When everything is commercialized, everything is monetized and commodified, including people.

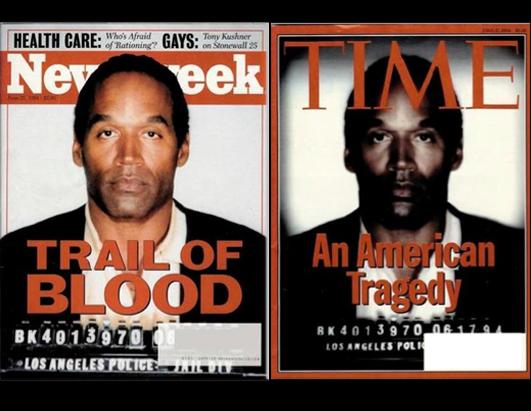

This means when it comes to images today, one is tempted to wonder about the motivation of those posting a picture. For example, look at the difference in how OJ Simpson was portrayed with the same photo in two different magazines.

Contrary to what our media outlets say, living in an image culture means that images are not neutral because there is always a context behind them. What is the context behind making OJ Simpson’s photo darker?

The danger of an image culture attempting to use images like speech is that it does not encourage rational thought and discussion. We cannot always verify whether the image is based in reality. We simply interpret the image from our specific context and argue over who has the right to interpret. This is fraught with problems.

The real question is, who benefits when we clash over the meaning of images? Whoever benefits is the arbiter and we do not always know who this person or entity is most of the time. We only know who liked and shared the image.

What do you think?